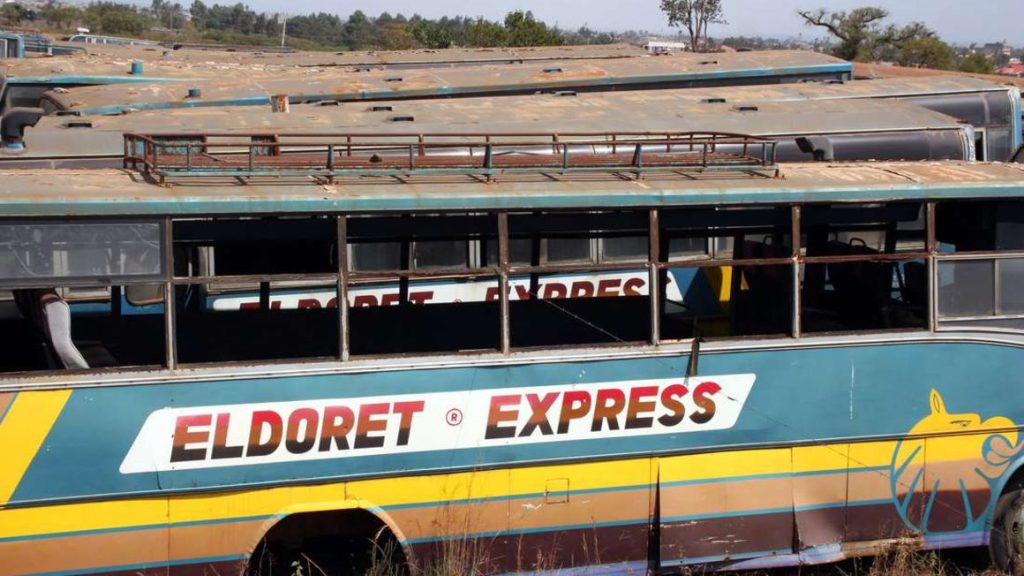

The dozens of Eldoret Express buses lying at various yards tell a story of the pain of transport businesses in Kenya. One such yard is located in Juja, Kiambu County.

Here, the Scania machines are parked too close to the other to fill the 450-metre perimeter field, and penetrating through is almost impossible.

Broken window panes, rims with no tyres, worn out seats, old registration plates, dust and cobwebs are the common denominators here.

They are testament of the time the vehicles have laid here, and also some assurance that they will never go back to the road. It is a graveyard for buses.

But even in their seemingly helpless state, the bus company’s management is overprotective and tightly guards them from any uninvited persons’ access.

“If my boss knew I had allowed you in, he would think I am selling you scrap metal. I would be in trouble,” the watchman at the Juja yard said when we visited.

And Juja is not the only facility where the company is holding the over 100 buses that have become worthless, although the management is hesitant to disclose the other locations.

ROTTING AWAY

The management, however, confirmed that it disposed of the vehicles after it became uneconomical to continue operating them, having been on the road for years.

“After functioning for some years, public service vehicles become uneconomical to operate. We dispose of about six vehicles every year,” said Mr Joseph Nganga, the operations manager at the company. To understand the situation better, we ran searches through Google Earth — a site that captures aerial images of places across the globe.

The images showed there were 56 buses occupying a 275m perimeter field (4,664 square-meter area) at Juja yard the last time the site was updated.

Travellers board an Eldoret Express bus in Kangemi Nairobi on August 8, 2020. PHOTO | SALATON NJAU

Travellers board an Eldoret Express bus in Kangemi Nairobi on August 8, 2020. PHOTO | SALATON NJAU

At the company’s farm in Kiungani, Kitale in Trans Nzoia County, about 80 buses littered the 500-metre perimeter compound (an area of some 14,000 square meters), at the time.

They are scattered all over the expansive farm, creating the view of some sort of an estate of many houses from above.

The company tries to maintain an upright posture, claiming to be matching on strongly. But as we speak to the operations manager, it is clear that the once formidable empire in long distance road travel is headed to its knees.

GOOD OLD DAYS

The loud absence of its vehicles on many roads compared to the way its Scania engines roared through hills and valleys in the 1990s and earlier years into the millennium have had many Kenyans suspecting that an empire they once treasured could be falling.

“Due to problems brought about by Covid-19, we currently have 53 vehicles on the road (35 buses and 18 shuttles),” Mr Nganga said. “During normal times, we operate with 60 vehicles and respond by increasing or reducing fleet depending on demand.”

He said the company has a capacity to operate a fleet of 100 vehicles, but depressing demand over the years has forced it to operate with 60 per cent during good times.

The management blames many things on its poor performance, even though there are Kenyans who believe that the company took its good time to adapt to a changing market in the transport sector — ultimately shooting itself on the foot as new matatu saccos emerged and grabbed the market.

In the end, the company has been left with a fleet of many buses that are as good as useless, many Kenyans having turned to shuttles, which fill quickly and save time.

Mr Nganga noted that the firm introduced shuttles last year to sustain various routes of its market.

“Changes in technology have affected travelling. Services such as M-Pesa have made many people who used to travel a lot in the past minimise movements,” Mr Nganga said.

LAND OWNERSHIP TUSSLE

He also cited devolution as one of the big factors that has affected the company’s operations, saying moving services to the people led to reduced movements.

But even with this reality, he said the company continues to buy between six and 12 vehicles yearly as it disposes of about six due to wear and tear.

“We have disposed of many vehicles because we started operating more than 30 years ago. We then identify those from which we can get good spare parts for the vehicles that are still on the road,” he said.

On debts the company owes outsiders, Mr Nganga insisted that they are manageable although he could not disclose figures.

“Nobody is chasing us. All the debts we have are manageable. We don’t have any bank coming after us to auction our property, We are servicing debts,” Mr Nganga said.

The company is also entangled in a land ownership tussle at the Court of Appeal, where it is fighting to protect its 640-acre land in Kitale. It’s been fighting for the property for more than a decade.

And as changes in the market diminish the firm’s fortunes while matatu saccos continue to gain, more buses that wear off will be joining Scania KAM 510M in Juja or her sisters in Kiungani, where they will rest forever.