When formal education was introduced by British colonialists in the early 20th century, there were no secondary schools for girls.

So when 17 girls outperformed boys, they had to be admitted to the best boys’ school before similar institutions could be established for them.

The British had initially intended for education to remain at the elementary level where Africans could learn to speak a smattering of English and do basic algebra even as they worked as farmhands and store-keepers in European farms.

But white Christian missionaries thought differently and went out of their way to build secondary schools for Africans, and open the way for them to pursue further education abroad.

That is how Alliance High School came into being, established by a consortium of Protestant churches. At the time, girls were not a priority on the missionaries’ to-do list, with the push to educate them yet to gain traction.

Alliance High was meant to be a school for the best performers from every corner of the country. Besides education, the institution intended to create a pool of Africans who would take over, if and when, the colony was free of British rule.

Indeed, the dream later came true when at Independence, nine of the 15-member Cabinet were Alliance alumni.

As it were, attitudes change with time and education for the girl child gradually became a reality. The same alliance of churches–the Christian Schools and Missions–that had established Alliance High led the charge by opening girls’ primary schools at Kikuyu, Kabete and Kamandura in Kiambu. These were soon followed by Weithaga in Murang’a, Tumutumu in Nyeri, and Chogoria in Meru.

There were still no secondary schools form girls and this proved problematic when Zibia Wangari from Kikuyu School and Lois Njeri from Weithaga School topped the national examinations in 1937.

No discrimination

The ensuing dilemma on what to do with these brilliant girls led to lengthy deliberations. A decision was finally reached that they should not be discriminated against on account of their gender and would be admitted at the only school reserved for the best performers–Alliance High.

So the class of 1938 had two female students in a boys-only institution. The school had no contingency plan to handle this novel situation so the managers built a dormitory for the girls and employed a matron to take care of them.

This was the start of a trend. Two years later, four girls outperformed the boys and were admitted to Alliance High’s class of 1940. From 1941 to 1950, there would be a girl in every Alliance class. The trend ended in 1951 with three girls the last to be admitted to the school.

After that year, Alliance Girls High School was fully established. It had opened its doors in 1948 with one Form One class, and the learners were the first to finish school in 1951.

At Alliance High, each of the 17 girls admitted remained a star, holding their own and refusing to be intimidated by the boys.

Three clearly stand out. First was Joan Wambui in the class of 1944-47. From Alliance, she proceeded to the prestigious Makerere University in Uganda–the only institution of its kind in East and Central Africa–where she graduated as a teacher.

She returned to Kenya and would be named the first African headmistress at Alliance Girls High. She is best known as Mrs Joan Waithaka and would go on to mentor many women who became the who’s who of society.

Roll of honour

Next on the roll of honour was Rebecca Njanjega who was in the class of 1951. Known better as Mrs Rebecca Njau, she also proceeded to Makerere. She is recognised as a novelist, poet, and collector of our national heritage.

Rebecca was a pioneer founder of one of the biggest and most famous art galleries in the country, Paa Ya Paa, that was based along Kenyatta Avenue before relocating to Kiambu Road.

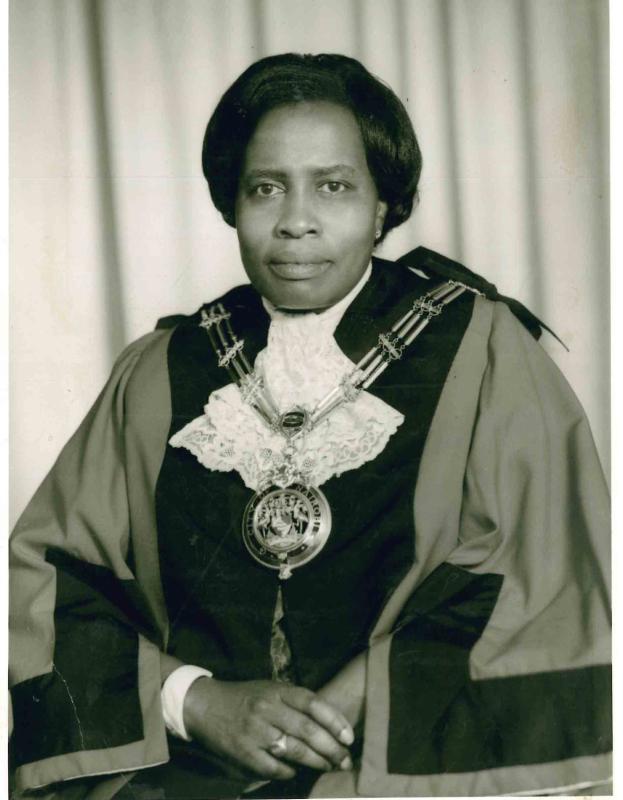

Last but definitely not least was Margaret Wambui who was in the class of 1947. Margaret was student No. 1,000 in the Alliance High register.

The eldest daughter of President Jomo Kenyatta would go on to become the first and only woman mayor of Nairobi. Margaret also served as Kenya’s representative to the United Nations Environment Programme and was a pioneer founder of the Maendelo ya Wanawake movement.

Imprisoned

Margaret also played a little-known but vital role by giving her father the strength to continue fighting after he had been imprisoned by the British and thought all was lost as he watched his world crumble.

This is best captured in letters exchanged between daughter and father when Kenyatta was in jail.

In one of the letters, Kenyatta wrote to his daughter: “Your great love for me consoles my heart … May we see each other in the eyes of the spirit. The letters from you comfort me and give me a reason to live one day at a time despite great reasons to lose hope and give up.”

At one point, Kenyatta suffered from a strange skin disease for which a colonial doctor prescribed vaccination for small-pox. Fearing poisoning, he threw the medicine given to him in a pit latrine and used a back channel to have Margaret buy medicine for him from a trusted doctor in Nairobi.

In his book Off My Chest, author and surgeon Yusuf Dawood–who was also the Kenyattas family doctor–reckons that Margaret was the apple of her father’s eye. He says she was one of few people who made Kenyatta laugh heartily even when in pain from diseases that crept in with old age.

Source: The standard